Warning: This story discusses graphic accounts of domestic violence, and other forms of abuse and violence, that some readers may find disturbing. If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, help is available through the National Domestic Violence Hotline at (800) 799-SAFE (7233).

The National Threat Assessment Center, or NTAC, released its latest publication, First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs: A Case Study on the Link Between Domestic Violence and Mass Attacks, April 23. It examines the link between domestic violence and mass attacks by delving into the deadly 2017 shooting at the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs in Texas.

A 26-year-old shooter killed 26 people November 5, 2017, including his wife’s grandmother, and injured another 22 churchgoers during a rampage just outside San Antonio, Texas. It was the deadliest mass shooting in Texas history.

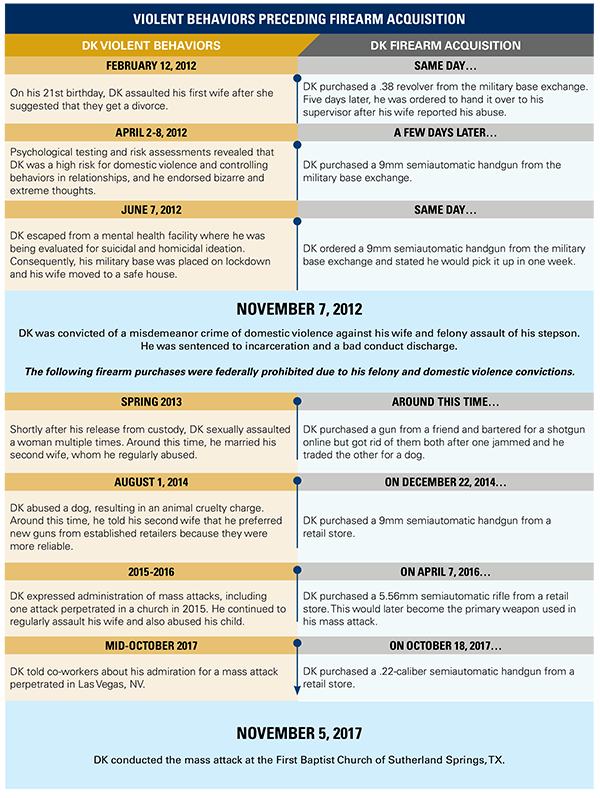

For years before the attack, the shooter engaged in repeated acts of domestic violence against his wives. He also had a long history of other concerning and criminal behaviors, including the harassment and sexual assault of numerous young women and girls, threats made to family, military personnel, and law enforcement, and the abuse of children and animals.

“We know from our research on mass attacks that there is a link between domestic violence and mass violence. This case study examines the background of a mass attacker who spent years committing acts of domestic and sexual violence against women and girls,” said U.S. Secret Service National Threat Assessment Center Chief Dr. Lina Alathari. “The analysis underscores that domestic violence does not always affect a single victim. These acts of violence can harm the broader community, and as such, there is a need for a whole-of-community approach to keep our neighbors, friends, and families safe.”

The Secret Service established NTAC to conduct research on targeted violence and provide guidance to public safety officials on preventing these types of attacks using behavioral threat assessment, which is an approach used by the Secret Service to protect the president and others.

NTAC has been conducting research to support the agency’s protective mission for over two decades. In October 2024, it released Behavioral Threat Assessment Units: A Guide for State and Local Law Enforcement Partners to Prevent Targeted Violence, highlighting 20 “assessment themes” frequently found in the background of assailants.

The shooter at the First Baptist Church, identified in the report only as DK, displayed most of these assessment theme markers, including DK’s history of domestic violence. In an earlier study, NTAC found that 41% of mass attackers had at least one incident of domestic violence in their background.

DK’s troubling behaviors began early on. He started preying on girls in his mid-teens. As a high school student, he frequently targeted younger girls in grade school, coercing 13- and 14-year-olds into sexual activities, and even raping them.

After graduating high school, he entered the military in January 2010 after lying about his drug use on his application forms. Just two days before entering active duty, DK was accused of indecency with a child, but DK was never interviewed because the witness withdrew from participation in the investigation.

He married a single mom with an eight-month-old son in April 2011. The pair met during DK’s high school years and reconnected while DK was stationed in Virginia.

Once married, they moved into military base housing in New Mexico. DK began to struggle in his military career. At one point, he told his wife, “My work is so lucky I do not have a shotgun because I would go in there and shoot everyone.”

DK was violent at home. He struck and shook his wife’s infant son, ultimately prompting investigations of child abuse against DK. The boy was placed into foster care.

The same day her son was taken, DK physically abused his wife for the first time. She told a relative about the abuse, who then reported the incident to military leadership. When questioned, DK’s wife declined to cooperate due to fears for her own safety, and the safety of military personnel.

DK continued to abuse his wife for the duration of their marriage. He often hit, kicked, or choked her. On multiple occasions, he threatened her life with a gun.

In late April 2012, his wife shared evidence of DK’s abuse with military investigators and informed them the couple would be separating. DK voluntarily admitted himself to a hospital for mental health treatment. In May 2012, a military team determined that DK should be held in treatment until he could be placed in pretrial confinement for child and spousal abuse.

However, DK escaped from the treatment facility June 7, 2012, prompting the lockdown of his military base and a manhunt. DK was found the next day at a bus station in El Paso, Texas — about 12 miles from the hospital where he escaped. He was then moved to a military jail.

DK’s wife finalized their divorce October 17, 2012. One month later, DK accepted a plea deal, admitting to the assault of his wife and her son. According to the report, he was sentenced to a reduced rank, a year of incarceration and a bad conduct discharge.

The conviction should have been entered into a federal database that would have precluded DK from purchasing a firearm from licensed dealers. This required action was never taken. DK was incarcerated for just five months after sentencing due to time served and good behavior.

After release, DK again began to assault women, including a 20-year-old woman that he raped on multiple occasions. He also kicked a 19-year-old pregnant woman that he was dating, prompting a miscarriage. Regardless, these two married on April 4, 2014.

The couple moved between Colorado and Texas five times over the next four years. Their first child was born in March 2015 in Colorado. That same year, DK began researching school shooters and mass attacks. He messaged a former military supervisor about his excitement for an attack conducted in a South Carolina church.

He also showed a fascination with firearms and attended gun shows. In April 2016, he bought a semi-automatic rifle from a licensed firearms dealer despite his prior domestic violence and felony convictions. This would later be the primary weapon used in the shooting at the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs.

By 2017, DK’s mental health was deteriorating. He moved his family into a barn apartment on his parents' property in Texas. He also regularly took away his wife’s birth control as a form of punishment, and she became pregnant with their second child.

In the months and weeks before the attack, DK demonstrated his plans for violence. In one note, he wrote, “I am the angel of death. No one can stop me.” He also made lists to delete his social media accounts, store things in his car when his wife wouldn’t notice and bury military dog tags for his son to find.

He also ordered high-capacity drum magazines from a store eight days before the mass shooting. He called this store daily to check on the status of his order leading up to his attack.

The target of his attack, the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs, was important to DK’s wife and her family. Her mother, brother and grandmother regularly attended services there. When he brought his family to the church grounds for a fall festival October 31, 2017, at least one witness believed DK was casing the church.

The morning of the attack, while his wife changed the children’s clothes, DK held her at gunpoint. He forced her to the bed and tied her up. Then, he retrieved his gear from a black bucket, put on black clothes, a tactical vest and a black mask with a skull logo painted on it.

When he arrived at the church, he shot at the building first from outside, then made his way in. He fired over four hundred rounds in the church. At one point, he told his victims, “Man guys, it’s really smoky in here.” His attack lasted over seven minutes.

As DK exited the church, a nearby resident who had heard the gunshots fired upon DK, striking him twice. DK returned fire, missed his target and fled in his vehicle. He called his wife and parents before crashing his vehicle. He then took his own life.

The troubling behavior in DK’s past should have provided an opportunity to intervene; however, according to the report, DK was never subjected to a behavioral threat assessment.

Prevention of domestic violence and mass violence is a community effort that requires collaboration between multiple community systems. This includes law enforcement, courts, mental health providers and domestic violence and hate crime advocacy groups, the report states.

“Everyone has a role to play in keeping our communities safe. It is important that individuals within the community share their concerns with those in authority, who must then take tangible steps to reduce the risk of violence,” the report says.

From 2012-2017, DK purchased at least five firearms, three of which were from licensed retailers. These retailers performed the necessary NICS (National Instant Criminal Background Check System) check, but the results did not flag DK’s felony and domestic violence convictions.

In direct response to this tragedy, Congress passed the bipartisan Fix NICS Act, which addressed gaps and required federal agencies to submit all relevant records in an accurate and timely fashion.

The Fix NICS Act, which President Donald Trump signed March 23, 2018, resulted in a substantial increase in records submitted to the national database, according to the Department of Justice.